SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket is an impressive piece of technology. It’s ultimate goal is to improve the cost and reliability of access to space and this is gradually being achieved through the reuse of as much of the rocket as possible.

Instead of the used first stage simply plummeting back into the ocean like prior rockets, SpaceX attempts to recover and reuse most Falcon 9 first stages. This involves the stage separating from the second stage and payload, flipping over and returning on a trajectory to a dedicated landing pad or autonomous drone ship where it then lands.

As you may have guessed, landing a rocket isn’t easy and requires a very high degree of precision, meaning that the control system must be very well tuned–i.e. it must preform within a very small margin of error and must not over react. Control communication latency must also be minimised.

Because of this, it is not at all possible for the Falcon 9 to be landed manually. Even if a human could respond with the delicate precision required to perform the operation, the communication latency of delivering that control input would be far too great for it to be delivered in time.

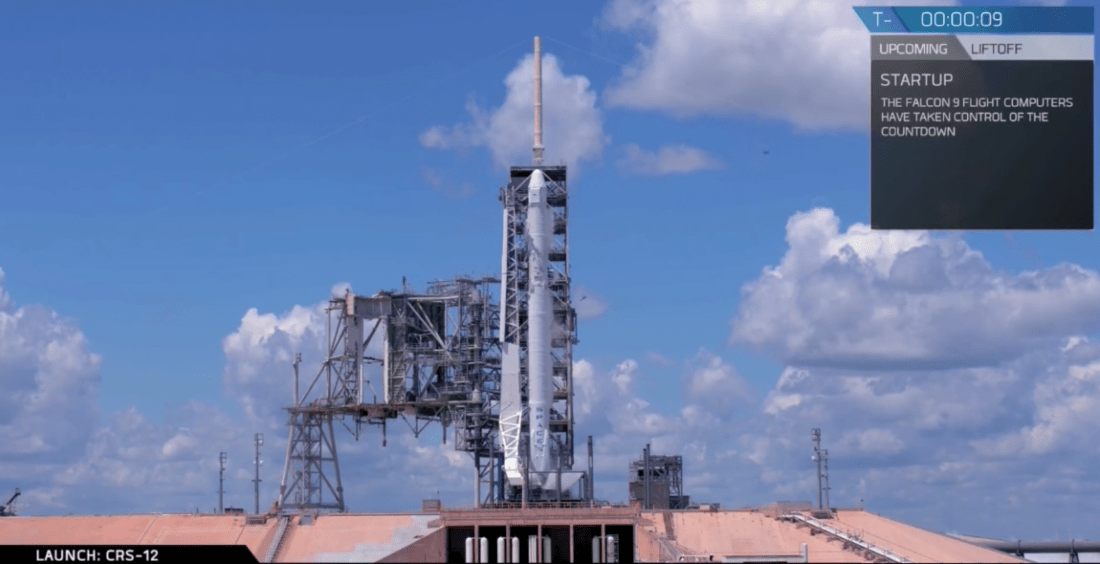

Except for the flight termination system which is triggered by an external radio command, the Falcon 9 is autonomous from T-10 minutes and from T-60 seconds onwards, the flight computer has full control. This computer is completely independent from ground computers and disconnects from everything before launch. (If you watch the webcasts, you’ll hear someone announcing “Falcon 9 is in startup”).

Because of the high energy cosmic radiation of space that can mess with computers, SpaceX uses a “triple-string” architecture where a vehicle has three redundant flight computers, any one of which can take control of the vehicle at any time should the others be malfunctioning. The Falcon 9 has 3 dual core x86 processors running an instance of Linux on each core. The flight software is written in C/C++ and runs in the x86 environment. For each calculation/decision, the “flight string” compares the results from both cores. If there is a inconsistency, the string is bad and doesn’t send any commands. If both cores return the same response, the string sends the command to the various microcontrollers on the rocket that control things like the engines and grid fins.

In addition to this, each Merlin engine is controlled by three voting computers, each of which has two physical processors that constantly check each other. These use a fault tolerant design known as an Actor-Judge system to provide triple redundancy.

The microcontrollers, which run on PowerPC processors, receive three commands from the three flight strings. They act as a judge to choose the correct course of actions. If all three strings are in agreement the microcontroller executes the command, but if 1 of the 3 is bad, it will go with the strings that have previously been correct. The Falcon 9 can successfully complete its mission with a single flight string.

The triple redundancy gives the system radiation tolerance without the need for rad hardened components. These commercial off-the-shelf parts and system-wide radiation-tolerant design also help significantly lower the cost of developing the vehicle. SpaceX’s Dragon vehicle uses a similar triple redundant system for its flight computers.

All flight software is tested on what can be called a table rocket. They lay out all the computers and flight controllers on the Falcon 9 and connect them like they would be on the actual rocket. They then run a complete simulated flight on the components, monitoring performance and potential failures. Engineers perform what they call “Cutting the strings” where they randomly shut off a flight computer mid simulation, to see how it responds.